Michael’s dying cat triggers his lifelong fear of final farewells

On the morning of the day Boo died, I sat beside her on the kitchen floor, spoon-feeding her. A few weeks before, she had lost the use of her hind legs, leaving her to spend most of the time lying on her side by her food tray, in and out of sleep.

Even as the end approached, I resisted making that appointment with the vet to cross her “over the Rainbow Bridge”, an expression I hated. It was assisted caticide, and I couldn’t bear it. “It’s not time yet, she’s not ready,” I repeated almost daily to my wife, Joan, who knew otherwise.

She was ready. What I had refused to acknowledge was that Boo was very sick. She was losing the lustre of her coat. She hardly purred. Her meows were weak. I knew she wasn’t going to improve, even though she always had – after falling off a hotel balcony, after the coyote attack, after winning bouts with allergies following our move to LA from DC.

A tiny female Abyssinian leaped onto Joan’s lap. That was Boo. She chose us

Deep down, I knew Joan was right. Boo was seventeen and a half and, as any pet owner can attest, you get to a point with an elderly dog or cat where you weigh the considerable costs of medical intervention against the benefits of minimal life extension. Boo had lived a good life despite the occasional trauma and brought us endless days of joy. With tears in my eyes, I finally called the vet and scheduled an appointment for the next afternoon.

Boo Janofsky, a gorgeous Abyssinian ruddy (the colour of her coat), came into our lives from a northern Virginia cattery. The lady who ran the place had dozens to choose from, and suggested a young male, but as we watched, dazzled and delighted by Abyssinians running and jumping all around us, a tiny female leaped onto Joan’s lap. That was Boo. She chose us.

We got her papers months later and they showed her registered name was Bojangles Her Royal Booness and that her father and grandfather were the same cat! “Selective breeding,” the cat lady explained, a process to refine certain characteristics. We were never quite sure what they were. Joan said it was Boo’s prominent ear set.

Between the two of us, Joan was the cat person. Boo was her third Aby, a breed she loved for the luminous colour of their coat, their over-sized ears and their innate athletic ability. Boo was a prototype.

I, on the other hand, had grown up with dogs, but Boo turned me into a cat person. Rather, a Boo person. I became her Primary, feeding her, brushing her, cleaning her litter box, scratching her head to turn on purrs. She returned the favours by making it clear I was her favourite, trailing me around the house, sleeping on my side of the bed, waking me with paw-slaps to feed her. Never mind it was 5am. Apart from Joan, I loved no one more.

Her demise was especially agonising because it took me back 25 years to the death of my mother. She had been in a car accident and spent the next three months hospitalised. Finally, the doctors gathered her sister, my sister and me – my father had died four years before – and told us there was nothing more medical science could do. The two women said, okay, it’s time to let her go, but the decision had to be unanimous. I was the holdout. Agony. I felt my mother’s death was not mine to authorise. I knew they were right, but I am not God. She was only 74.

Saying goodbye was almost impossible. For one thing, she was in and out of consciousness and for another, I have deep-seated separation anxiety, residue from an early childhood shaped by a father who was in and out of hospital with heart attacks. It programmed fears and anxiety onto my psychological hard drive.

As it turned out, saying goodbye to my mother was impossible. After I cast the deciding vote, the doctors said she would go peacefully, probably within 24 hours. My aunt and sister said their goodbyes to her, then returned to their homes in other states.

Frightened man-child that I was, I stood at the door of her room, paralysed. Rather than sit by her bedside for a while, I waved from a distance, then left. With a chance to confront my deepest emotional monster, I cowered. It was the worst moment of my life, the worst of me. The hospital called the next morning to say she died overnight. I am still haunted by my hesitation that day. The monster lurks.

Joan and I do not have children. Boo was our child. We loved her equally even if Joan was convinced Boo loved me more. “I feed her,” I explained. But as her condition worsened over those final weeks, I felt myself receding from her. The monster was coming out of hibernation. I knew Boo was fading; I couldn’t face it. As I withdrew, Joan moved in. She sat beside Boo, petting her, drawing out a tiny purr. She carried her around the house, talked to her, anything to comfort her.

The last morning came. Despite her ailments, Boo ate her breakfast with the usual gusto – maybe she was still okay? – then, we all went about our morning routines. Joan retreated to her desk in the converted garage; I, to my desk in the den. Boo plopped down beside her tray.

A few hours later, I was exercising on the treadmill when Joan found me. “Boo is dying,” she said.

“No,” I insisted. “She ate a good breakfast. She’s not dying.”

“Yes, she is.”

Joan left, and I put the thought out of my mind and continued exercising. Ten minutes later, she came back with Boo in her arms.

“She’s dead.”

I climbed off the treadmill and wept.

I can’t help but think Boo knew all along how her final days were affecting me, that she knew I feared her leaving us, that I hated making that appointment, that I knew I could not be in the room when the vet took over, my monster in full command.

Yet somehow – magically, spiritually, mystically – Boo had taken charge. She rescued me. In the ultimate act of love, she took agency of her end, dying at home, in Joan’s arms, no sterile vet’s office for her.

For Joan, their final communion was a joyous gift. “I know Boo loved me,” she said. “We locked eyes. She knew I was there and it was okay to let go.”

I still cry now and again. It’s hard to look at the empty place in the kitchen where she spent her final days. But her death and the sadness it provokes was a wake-up call, too. Losing a beloved pet is difficult enough; lugging around the emotional baggage that it triggers makes it worse. Joan is already shopping for a pair of Abyssinian kittens. I’m shopping for a shrink.

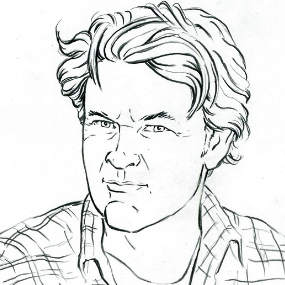

Michael Janofsky is a writer and editor in Los Angeles. He previously spent 24 years as a correspondent for The New York Times