Punk rock band The Murder Capital have a lot to say

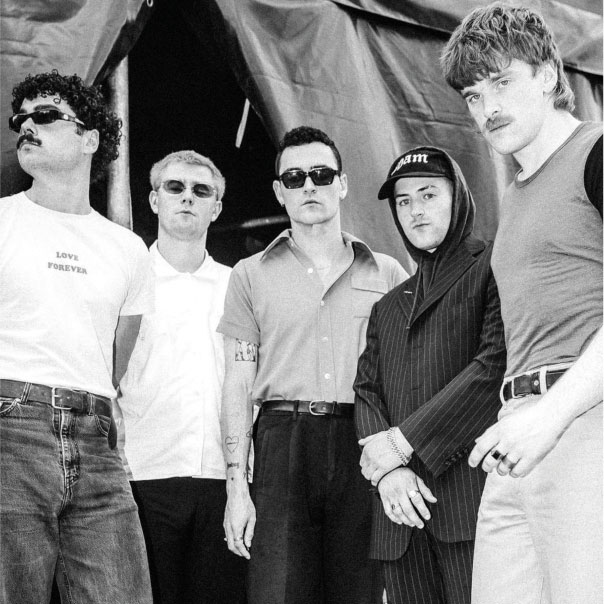

A few summers ago, at End of the Road Festival, I stood in the muggy heat of a marquee to watch a band named The Murder Capital. I didn’t know a great deal about The Murder Capital at the time, but I had seen them backstage, milling around by the door to their portacabin sporting high-waisted suit trousers and truculent haircuts, and I had wondered at their demeanour. In lieu of the usual summer festival gaiety, they wielded a mood we might sum up as: “We aren’t here to have a good time; we’re here because we have something to say.”

When they took to the stage, they did so with the energy of Brighton Rock’s Pinkie Brown marching into a seaside tearoom and demanding service. The crowd looked somewhat ruffled, and thoroughly delighted. The band hurtled through a short, snarling set made up of the tracks that would become their debut album, When I Have Fears. And then they stormed off. As if they had an appointment to set fire to something. It was the most thrilling and beautiful and compelling thing I had seen in months.

The Murder Capital was formed in Dublin in 2018; five young men at music college, spurred to make music that could effect change, that might capture how it felt to be young and restless, that was honest about drugs, alcohol and mental health, but also found space for a kind of romance. This January they return with their second album, Gigi’s Recovery, a more textured and lyrically vulnerable record than its predecessor. We might file their music under “post punk” or compare it to Joy Division or the Bad Seeds or Radiohead, but really it belongs to them, and to these times and to the land they are from; songs seared with fury at inequalities witnessed close to home, lyrics turned dark with grief and loss. Music that is brutal and elegiac all at once.

It would be foolish to suggest that Ireland’s music scene ever waned, but in the last few years it has certainly soared with a new energy. The murder Capital’s contemporaries – artists such as Fontaine’s DC, Lisa O’Neill, Lankum, Gilla Band, Just Mustard have brought a fresh hard beauty to the sound; folk-diddlery giving way to something more brutal, Irish lyricism bound with tough-edged colloquialism. Some while ago, I spoke to Philip King about this fresh resurgence in Irish music. King is a musician, filmmaker and broadcaster who helms Other Voices festival in Dingle, where acts such as The Murder Capital and Fontaines DC enjoyed early support.

It was a golden age, he told me, perhaps unparalleled in terms of breadth and diversity, and when I asked him why that might be, he pointed me in the direction of the Irish song collector Frank Harte. “Harte said: ‘If you want to know the fact, consult the historian or the history books,’” King told me. “If you want to know what it felt like, ask a singer.” Artists who are writing, singing, playing and recording in Ireland right now are dealing with what it feels like to be of this place. Which is a changing country.”

That change, King explained, is manifold; a melding of progress and restriction – the right to choose, gay marriage and immigration all contributing to a richer and more open culture, but young people find themselves frustrated by the inability to find financial momentum. “We’ve come a long way in a hundred years since independence,” King said, “we have a modern, pluralist, diverse public that has many, many difficulties, and with a younger generation of people who feel excluded from the business of being able to buy a house.”

As Ireland has recalibrated in recent years, modernising, reimagining, tussling with ideas of identity, with its past and present, a discontent has been gathering – specifically a sense of generational exclusion. That this should surface so viscerally in the music emerging from this country is no surprise. This is a culture sown with rebel songs and protest poetry, with a belief that ideas beget art, and art begets feelings, and feelings stir change. To watch that happen in real time feels something like an honour. “What music does,” as Philip King told me, “is it makes all sorts of things gradually become physical. Musicians are the heralds of the future.”

Laura Barton is a writer and broadcaster. Her book, “Sad Songs”, is out next year