Katherine Rundell didn’t believe in love at first sight… until a recent encounter with a pangolin in Zimbabwe. Known as the scaly anteater (because of its diet and the fact it’s the only mammal with scales), Rundell notes that this basic description falls short in reflecting the strange glory of a creature whose scales are “the same shade of grey-green as the sea in winter” and whose face puts her in mind of “an unusually polite academic”. The female she met lives in a wildlife conservation project near Harare. Her keeper spends ten hours a day walking with her from anthill to termite mound, watching her devour around 20,000 insects a day. If the gap between mounds is short he will let her walk. If not she will return to him to be carried, placing one hind foot onto his shoe to allow herself to be more easily lifted onto his shoulder.

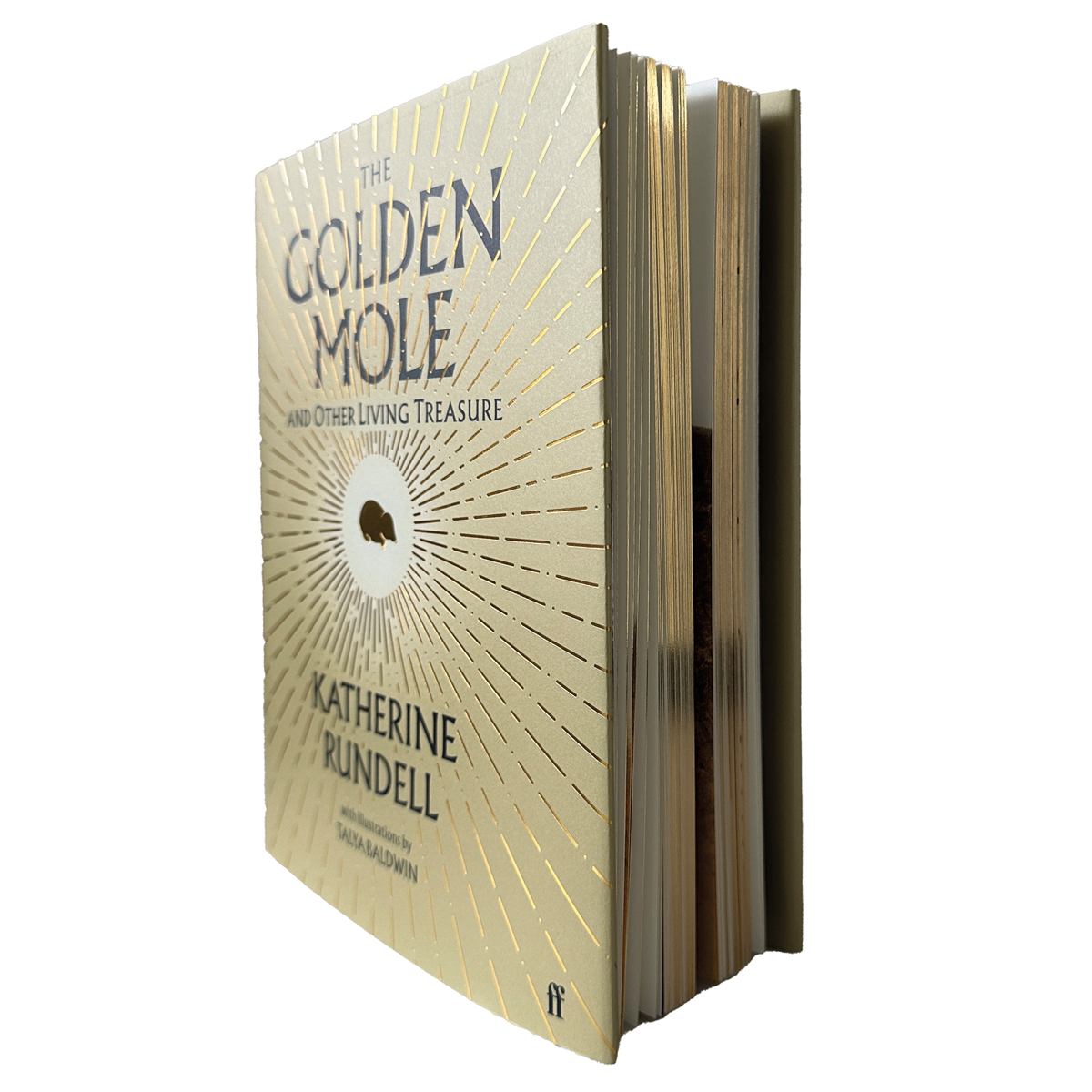

In her new book, The Golden Mole And Other Living Treasure, the 35-year-old children’s writer, John Donne biographer and academic invites readers to rejoice in the wonder of 22 extraordinary creatures, including her beloved pangolin. Its tongue, she writes, is longer than its body and is kept “tidily furled” in an interior pouch near its hip. She teaches us the name “pangolin” comes from the Malay word penggulung (roller) because they curl themselves into tight balls when threatened. A defence mechanism which must have proved effective when they came into being 80 million years ago (compared to our mere six million). But one which now, Rundell laments, “has made them easy prey to humans – rather than offering protection, they render themselves neatly and readily portable.”

Over the phone from her home in London, Rundell’s voice drops to an urgent whisper as she reminds me “how rare these astonishing creatures are now. At immediate threat of extinction. They’re one of the most trafficked animals in the world and they are so precious!”

Two of the eight species of pangolin are now deemed critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. Beijing customs have seized over a tonne of scales being shipped into China for unproven “medicinal” use: a fact Rundell finds “so exhausting, so dreary that it’s difficult to fathom”. It’s not just their scales that are in demand. The roasted flesh of these personable pine cones is believed to stimulate lactation and boost blood circulation. Rundell quotes a chef from Guangdong who told the Guardian that: “We keep them alive in cages until the customer makes an order. Then we hammer them unconscious, cut their throats and drain their blood. It is a slow death.”

Rundell sighs. “As I say in the book, to see a living pangolin is such an extraordinary delight. It is one of the great bafflements of our age that there are people who can look at the oncoming [environmental] crisis, the oncoming potential dark age of a barren world, and be… untroubled. It’s bewildering to me.”

An appreciation for the wild – both around and inside of us – has always been central to Rundell’s fiction. Born in Kent in 1987 she spent ten years of her childhood in Zimbabwe. She told Newsweek that: “In Zimbabwe, school ended every day at one o’clock. I didn’t wear shoes, and there was none of the teenage culture that exists in Europe. My friends and I were still climbing trees and having swimming competitions.” Her father’s work as a diplomat then saw the family relocate to Belgium when she was fourteen and she struggled with the more structured, urban lifestyle.

“Growing up,” she tells me in a strangely careful RP that keeps reminding me of Celia Johnson in Brief Encounter, “I saw grass snakes walking the dog. I saw monkeys in the streets. The moment you got out of the city there would be wild herds of zebra. To see them on the drive to a friend’s picnic is such a vast delight.”

She began work on first children’s book, The Girl Savage (2011) the day after she turned 21, drawing on her barefoot Zimbabwean childhood. She had just begun a seven-year prize fellowship at Oxford’s All Souls College, awarded after fifteen hours of exam papers and a viva. There followed a decade of scholarly research into John Donne, which culminated in her Baillie Gifford Prize-winning 2022 biography Super-Infinite, in which she describes the seventeenth century poet with the same conversational flair as the creatures in The Golden Mole. At 23, she writes, he was “all architectural jawline and hooked eyebrows,” wearing “a hat big enough to sail a cat in”. She’s evangelical about his “electric intellect” and passions, while acknowledging his occasional cruelty and his “angry, bitter corners”.

Through the years she was beavering away on Donne, Rundell kept delivering delicious stories for children. In 2013 there was Blue Peter award-winning Rooftoppers, (a tale of urban climbing based on Twelfth Night). Then The Wolf Wilder (2015) and the Costa book award-winning The Explorer (2017) about children surviving a plane crash in the Amazon jungle. My ten-year-old daughter has heard the latter on audiobook so many times she knows chunks of it off by heart. She’s attached to the complex human characters, but most smitten by the baby sloth they adopt. And she was deeply affected by the advice given to the children at the end: “When you get home, tell them how large the world is, and how green. And tell them that the beauty of the world makes demands on you. They will need reminding. If you believe the world is small and tawdry, it is easier to be so yourself. But the world is so tall and so beautiful a place.”

“If you believe the world is small and tawdry, it is easier to be so yourself. But the world is so tall and so beautiful a place”

The Golden Mole sees the author acting on her own advice. Its short, perspective-spinning essays, quietly illustrated by Talya Baldwin, encourage us to interrogate our relationship with the animals described. An embarrassing theme emerges. The human tendency to underestimate the complexity of our fellow planet-dwellers. We’ve projected our own narratives onto storks, narwhals and bats. She bounces these critters against tales of human writers, generals, scientists and merchants. Homer, Mary Queen of Scots, Lorenzo De Medici, William Caxton, Ivan the Terrible and Ernest Hemingway all get name-checked. “We have been allowing ourselves to believe that the living world – the great parliament of the inhuman – is much more simple than it is. We have not given it the care and the respect it deserves.”

She says: “I’m keen to impress on readers that while our knowledge is a formidable and beautiful thing – and I am in awe of the scientific progress we have made of the past 150 years – we are still definitely wrong about many things. As wrong as Pliny was, when he thought that hedgehogs were rolling in grapes like 1970s cocktail waiters.”

As a curious kid, she’d end up mulling over the zebra herds she saw. Why were they stripey? “We used to think that as their large predators were colourblind the stripes were camouflage, mimicking the grass. Now new research suggests the stripes are there to deter biting ticks which cause fevers and death. The spangle effect may put off a biting insect. We imagined the greatest threat to zebras was the big predators because that was dramatic for us to observe, but of course the greater threat may be sickness. We are still making mistakes which are based on our old narratives.”

Earlier this year Lucy Cooke clarified just how much British, Victorian ideas of gender roles had influenced our understanding in her brilliant book Bitch: A Revolutionary Guide to Sex, Evolution and the Female Animal. She reminded us of the female birds committing adultery and the female orcas leading and teaching their pods long past menopause. “Our mistakes are so revealing aren’t they?”, says Rundell. “One of our desires was to make the subjugation of women look natural and of course we were utterly wrong. Binary sex roles are in no way as clearly drawn as we had imagined and they are by and large the dogma of – amongst others – Charles Darwin.”

Rundell ends our call – as she ends her witty, perceptive and evangelical book – with a plea for more understanding. “We don’t even know how many species there are in the world,” she says. “Estimates range from around two million to 100 million, although the current consensus is around 8.7 million – of which the vast majority will turn out to be invertebrates. We stand on a planet that is infinitely richer than any human knows and that’s an extraordinary thing. The idea of my book was to bring in front of people things like 500-year-old Greenland sharks (which many people haven’t heard of) and then things like hedgehogs, which they think they know about, and showing them: it is all so much wilder, stranger, more intelligent, beautiful and multifaceted than we thought.” Once her readers have “agreed to astonishment” she asks them to go further and find love. She argues that “love, allied to attention, will be urgently needed in the years to come.”

Helen Brown is an arts journalist writing regularly for The Daily Telegraph, The Independent, The Financial Times and The Daily Mail