Small town sleaziness next to wilderness

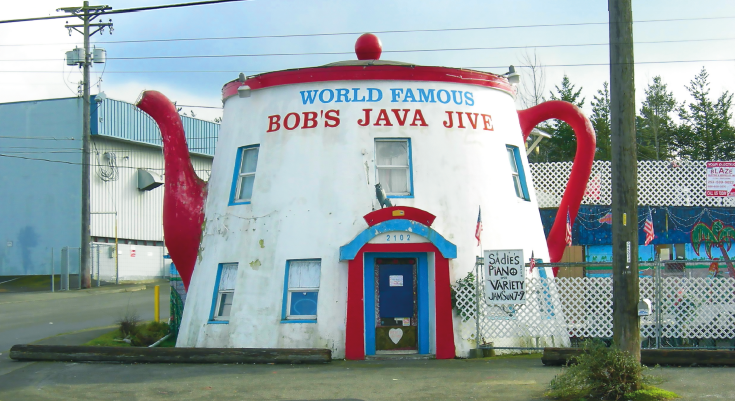

The first time I spoke to a stranger about sleaze was in the parking lot of a bar shaped liked a coffee pot. Bob’s Java Jive looks like what it once was: a roadside attraction that existed in the middle of nowhere particular to the mid-century American highway system. But the highway moved and the mid-sized city of Tacoma, Washington grew. Inside Bob’s Java Jive there’s tiger print along the bar and loaded fries on the menu; outside, it’s surrounded by the pea-gravel lots and corrugated roofs of the industrial Pacific Northwest, sodium lights bleeding into the fog.

It is a joyously, undeniably sleazy place.

“But why,” I wondered to some guy dressed like all the some-guys of my youth: that sweatshirt, that baseball cap, tattoos, a blue spot on his thumbnail where he’d hit it with a hammer. “What makes it sleazy?’

“This wilderness,” he said gesturing out at the lot filled with off-duty school buses and at the heated self-storage units.

South Tacoma is not the wilderness, but this guy had a point. Bob’s Java Jive is sleazy because it retains something of its roadside attraction past, some link to being the one place in miles of nowhere where you can get a burger. There’s something about proximity to the blank spots on maps that brings out the sleaze in everything and everyone and every coffeepot-shaped diner-turned-dive bar.

I live in Germany now, and it surprises me how deeply I miss the wilderness of the American west coast. I dream about it often. I find it uncomfortable to think about, both because of the acuteness of my yearning and because the wilderness is simply too big to think about comfortably.

But if I want to consider the American wilderness, and American obsession with wilderness, on a more manageable scale, I think about sleaze.

The wilderness itself is not sleazy; it would be pretty silly to suggest that nature was sleazy. But that’s not because people, at least not Americans, think it’s silly to attach a moral value to nature. We do it all the time. Nature is pure. Nature is untouched. Nature gets assigned those positive, virginity-adjacent qualities Americans are so fond of doling out to the things we value.

But once you put a cluster of buildings next to the wilderness you start training a beady, small-town eye towards them and invariably sleaziness appears. People living next to the wilderness are never as pure, as untouched, as the wilderness itself.

When people are deemed sleazy, it’s because they exist on the line between wild and tame. We wouldn’t call a hardened criminal sleazy. We’d reserve that term for someone whose criminality retains a veneer of respectability, or whose respectability is tarnished beyond full repair.

People like talking about sleaze, especially outside of bars. They like fumbling over its meaning. The definition of sleazy – marked by low character or quality – is maddeningly vague, both rigidly Puritan and with the slippery permissiveness of a mythical riddle. Sleaze exists, it seems, in the eyes of the beholder.

I’ve always had a weakness for men I find sleazy, and talking with them about sleaze is a refracted thrill, like talking analytically about sex with someone you want to have sex with.

I like egging these men on. What’s sleazy? Bob’s Java Jive. Why is it sleazy? The wilderness. The leopard-print. The ceiling that hasn’t been painted since 1962. That overpowering smell of Pine-Sol in the bathroom, like the smell of someone unwashed but wearing cologne.

That’s the proximity of wilderness again. That which we judge to be sleazy is mended with twine and held together with safety pins. “Sleazy” doesn’t have to be synonymous with “janky,” but it can’t be new or pristine in its upkeep. The edge that sleaze rides is the edge of the world: resources are scarce and expertise is hard to come by. Forget streamlined professionalism, you need that frontiersman spirit, the ability to darn socks and build a shed and kill the animal and also cook it.

When it comes to sleaze, more is more.

This is the spirit of the first known usage of sleazy, in a 1644 philosophical treatise on the brain. It’s a bizarre and repulsive text. Sir Kenelm Digby imagines the brain as mainly liquid, but filled with stringy formations similar to the bacterial “mother” strands that form in vinegar. Some of these strands, he hypothesises, are:

“hairy or sleasy, that is, have little downy part, such as on the legs of flies, or upon caterpillars, or in little locks of wooll; by which they eaßily catch and ßtick to other little parts of the like nature, that come neer unto them”

Sleazy, in other words, attracts without prejudice. Sleazy is promiscuous, adhering to everything, making sense of the world through its debris.

Of the three examples listed, I like flies’ legs the best, and think they’re the most representative of sleaze. Sheep are woolly for the same reason caterpillars are fuzzy: protection. Fly hairs, however, are designed to deliver maximum sensory input. The bristles that cover their bodies –including on their legs – are covered with taste and smell receptor cells. A fly rubbing its limbs together is swirling a glass of brandy, inhaling, taking a sip, aerating, cleansing its palate, going back for more.

“I am sleazy,” said one guy and he sounded so pleased with himself, and I though oh dear, no you’re not. It’s impossible to be sleazy and so completely satisfied.

Towns near wilderness exist to satiate people’s appetites. This is what makes proximity to the wilderness sleazy: people coming back, full of appetites, looking to absorb flavours as indiscriminately as a fly’s leg hair. Their tastes are not rarified; they’re ravenous. Or they’re leaving, stocking up, one last hurrah, for the wilderness. They’re disappearing for a little while, or flirting with the idea of disappearing for a while.

When I was working in remote Alaska a friend of mine would prattle on about nachos. What she wanted was excess on her nachos. She wanted to have everything anyone could possibly put on a bed of tortilla chips. The list of toppings on the nachos she would eat when she went back to town grew and grew, becoming an addled refrain like that children’s memory game: Sally went to Chicago and brought along a cat, Sally went to Boston and brought along a bear, Sally went to Anchorage and brought along an alligator.

Once I was talking about sleaze with a guy who alternated taking bites of omelette with drags of a cigarette. The man said goodbye and left my apartment. I went out to the balcony to clear away the plates and ashtrays and saw him on the street, peeing on a tree. I audibly gasped; a schoolmarm. Why didn’t he go into the bathroom before he left? I’ll never know.

He was sleazy, in that way the last town before the mountains is sleazy, or in the manner of Bob’s Java Jive. An appetite that strained the boundaries of good taste, exhaling cigarette smoke through a mouthful of egg. Forgoing civilisation (my bathroom) for the wilds (the linden tree on my street). And of course, being observed by someone shocked at errant behaviour.

My Puritan gaze, narrowed in judgement. Retreating with a stack of clattering dishes, to sit on the sofa, turning over the puzzle of some mildly transgressive, vaguely wild behaviour. That made it sleazy. But the sleaziness really had nothing to do with what was happening in the wilderness, and everything to do with me observing whatever I called wilderness from within my well-lit, domestic sphere. The call of sleaze was coming from within the house.

Rebecca Rukeyser is from northern California and currently lives in Berlin. Her debut novel, “The Seaplane on Final Approach” (Granta Books, out 9 June), was described by TIME Magazine as “a best book of summer 2022” and “a meditation on sleaziness”

Henry Dimbleby

Your email address will not be published. The views expressed in the comments below are not those of Perspective. We encourage healthy debate, but racist, misogynistic, homophobic and other types of hateful comments will not be published.